By Frank Edima

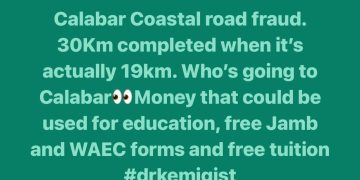

While I was scrolling through my news feed on Facebook, I saw a post by a retired Nigerian American Journalist, Kemi Talks, her post stirred quite a storm online.

In questioning the federal government’s proposed coastal highway project a conversation well within her rights as a citizen in a democratic society she posed a rhetorical question that landed differently: “Who is going to Calabar?”

It was not the coastal highway debate that drew my attention, it was her stereotype message about Calabar. As a concerned citizen and advocate for sustainable development, I have always held the view that every Nigerian should have the right to interrogate national projects. However, it was the implied irrelevance of Calabar in her statement that struck a deeper nerve, maybe annoying.

There comes a time in a person’s life when silence is no longer an option not because of politics, but because of shared identity, who we are, our heritage , what we represent, this is one of those moments.

Kemi Talks, Yes, people go to Calabar!!!

They go for business, tourism, research, investment, and culture. The city is far more than a stop on a political itinerary or a line on a map. It is a vibrant hub of heritage and hospitality, the first capital of Nigeria, the country where you practiced journalism with the Nigerian Tribune, a destination that deserves far better than to be reduced to a footnote in national discourse.

Calabar is home to the world-renowned Carnival Calabar, Africa’s biggest street party, which draws thousands of tourists and creatives from across the globe every December. It is also the home to one of the continent’s largest wildlife reserves, as well as a major field site of the National Conservation Foundation, this underscores the city’s importance in global environmental research.

It is a place of peace, culinary brilliance, and historical depth. From the days of the old slave trade ports to its current role as a hub for eco-tourism and cultural preservation, Calabar has always mattered. Yes it does. Which is why flippant remarks about its relevance especially in public discourse should not go unchallenged.

Words matter. They shape perception, and perception, in turn, shapes investment, migration, policymaking, and public sentiment. When a city is reduced in perception, its opportunities shrink, its youths feel invisible, and its potential is overlooked.

Kemi as a retired Nigerian journalist whose root in journalism should have known that this is not just about Calabar. This is about every city she covered, and town whose stories have been ignored or misrepresented. It is about how we must learn to guard our narratives before they’re hijacked by ignorance or indifference.

For years, my work with the Bakassi Fish Festival has been rooted in this exact principle, telling our stories, sharing our testimonies, our shared values before others rewrite them. Our people, our places, our traditions deserve recognition on our own terms.

I don’t know why a screenshot of my comment was circulated, but I do know this: I stand by my words. Calabar is more, and those of us who love her must keep telling her story.

It’s time the media in Calabar, and all who care about the power of narrative, step forward. This is more than a clapback. It’s a call to action.

Let us shape how the world sees us.

Because Calabar is more…

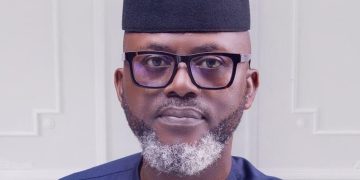

Frank Edima is a Strategist, cultural advocate, media professional, and Founder of the Bakassi Fish Festival. She writes from Calabar.